Show notes, links, and transcript:

Visit Marcie’s website ScientistsInTheMaking.com

Follow Marcie on Twitter/X @SciInTheMaking

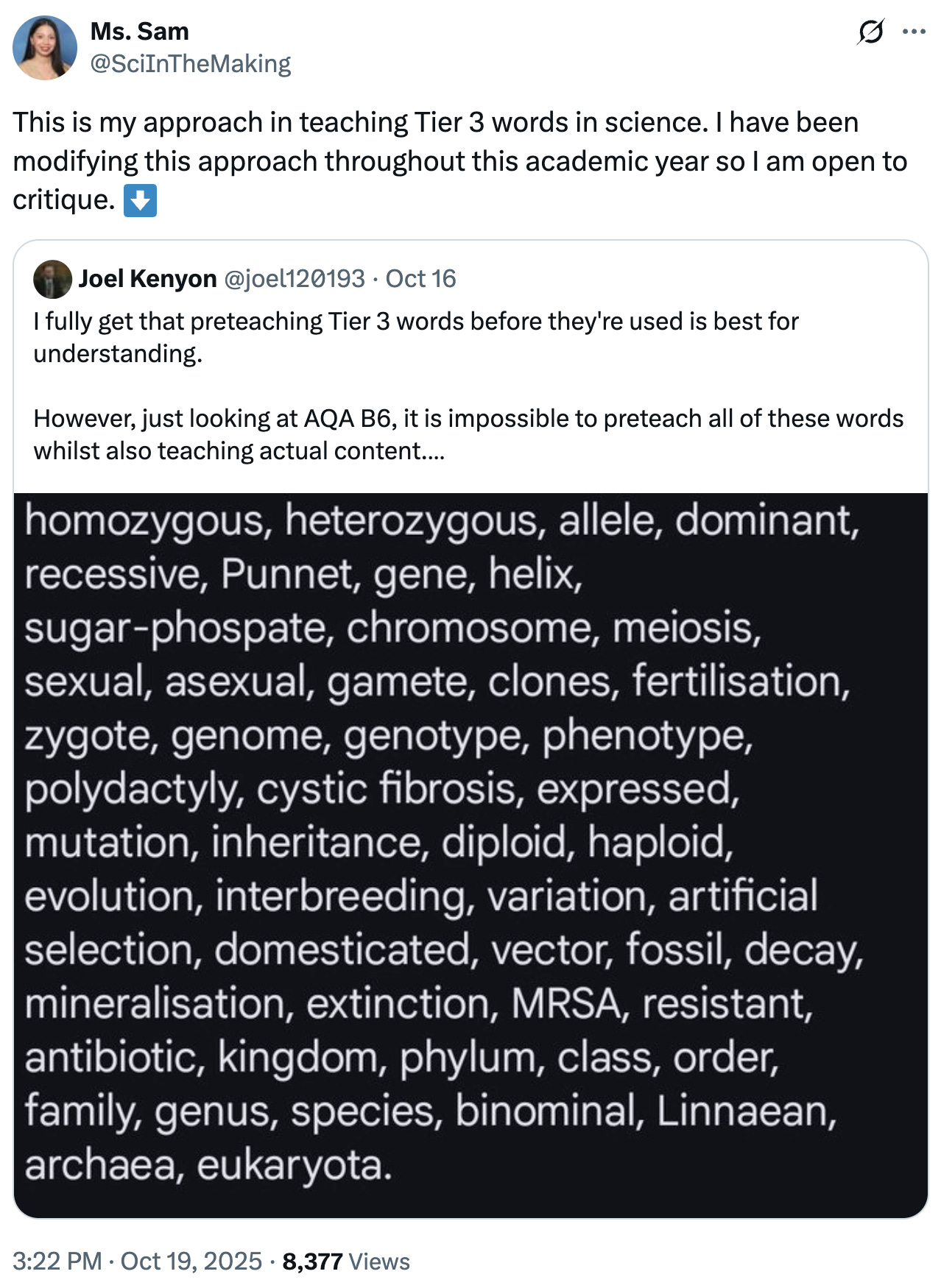

Teaching Tier 3 Words in Science—thread on Twitter/X

FASE Reading from Teach Like A Champion

Schools Are Accommodating Student Anxiety — and Making It Worse, by Ben Lovett and Alex Jordan

Brett Benson: @SoLInTheWild on X & SoL in the Wild on Substack

FASE Reading Plug and Play training from Teach Like A Champion

Additional notes, quotes, and links on tiered vocabulary instruction

Full Transcript:

Justin Baeder (00:00):

Welcome to the Teaching Show. I’m Justin Baeder and I’m honored to welcome to the program Marcie Samayoa, AKA. Ms. Sam on X.

Marcie, welcome to The Teaching Show.

Marcie Samayoa (00:11):

Hi. Thank you for having me. I’m excited to be here.

Justin Baeder (00:14):

Well, I’m excited to talk about some strategies that you have been sharing on X or Twitter lately around FASE reading, F-A-S-E, reading from Teach Like A Champion and teaching Tier 3 vocabulary. So tell us a little bit about yourself, what you do, and then we can get into it.

Marcie Samayoa (00:32):

Yeah, so I’m a high school chemistry teacher in Los Angeles, California. I have been in the classroom for 10 years, and for the past, I would say five years, I have been trying my best to implement cognitive science principles into my lessons, and I have seen a huge academic gains, so I’m more than excited to share those practices with others.

Justin Baeder (00:57):

Wonderful. Well, let’s start with FASE reading or faze reading. Just briefly tell us what that is and how you use it in your classroom.

Marcie Samayoa (01:05):

So FASE reading is a way where we encourage students to read, and the way we do that is the teacher models joy and expression when they’re reading. That way that joy can be transferred to the students.

And also I think it’s very important to show students how to express reading. For example, every time you see a comma, you pause. Every time you see an exclamation point, you say it in an excited tone, or every time you see a question, you read it as a question if you see the question mark. So it’s something that you need to model to students because unfortunately they haven’t had that model to them as much previously.

So that’s what I do, and while we do the reading as a class, I maintain attentiveness by cold calling students. That way they know that they all have an equal chance to be called upon to read out loud.

Now, I know this might be controversial for some educators. They bring up anxiety and that sort of stuff, but I think if we do it in a safe learning environment, we can encourage students to try to read out loud and therefore eventually get them to become better readers because the only way they will get better is to actually do it. Yeah, that’s pretty much what FASE reading is. I could go into more detail if you want me to.

Justin Baeder (02:39):

Yeah, well, I’m glad you mentioned cold calling and anxiety. I was just reading an article from Teachers College Columbia about how when we avoid calling on students out of a concern for anxiety, often we make that worse. And there’s of course a lot of research on this and a lot of experience in the teach, like a world about setting students up for success so that we’re not making students suffer in any way by calling on them.

We’re being thoughtful about that, but we are getting them involved. We are calling on students to actively participate and FASE is an acronym: Fluent, Attentive, Social, and Expressive, in the Teach Like a Champion lexicon. And I know Doug is an English teacher, and some of the descriptions of how to use that practice are written with literature in mind or other types of text. But you’re using this with pretty heavy duty science text, is that right?

Marcie Samayoa (03:38):

Yes, I am. And the reason for that is because we do want to expose students to rigor. That’s the only way that they are going to get better. But you do it in a way where you provide them support, and that’s where FASE reading comes in. So for example, by modeling how to read it through expression, you show students exactly what is expected of them.

So when students know what is expected of them, their anxiety goes down. And then in addition, if students still feel anxiety, what students can do, or what I can do is I can prepare them ahead of time. Usually you don’t want to let students know that they’re going to be called upon, right? Because you want everybody to be attentive. You want everybody to just know that it’s equal.

However, when you have students with IEPs or students with severe anxiety, what you can do to calm that down is you can tell them, Hey, let’s practice reading this one sentence together and let’s practice it over and over and over, and then during class I’m going to call on you. Okay. And you’re going to do so good because we practiced, and that way you can get buy-in.

Now, I just want to be very straightforward. This was not my idea. I actually got it from another educator, a fabulous educator on X. His name is Brett, and he has a blog known, I think it’s SoL in the Wild.

So yeah, so that’s where I learned that strategy. So just because you’re cold calling students doesn’t mean that you’re making them experience more anxiety, we’re just setting them up for success.

Justin Baeder (05:20):

Absolutely, absolutely. And there was a question that I saw your response to from a British educator, Joel. He was talking about how often with vocabulary, especially vocabulary that would be very unfamiliar to students, if we’re going to read through say, a chunk of a biology textbook or an article about chemistry, often there is very dense vocabulary, and so much of it may be new to students that we worry that kids are going to get lost immediately.

If we start reading this, the fluency is going to be difficult. And there was some discussion back and forth about pre-teaching and things like that, and Joel said, if I pre-teach this vocabulary, that’s essentially going to be pre-teaching the entire curriculum. So how do I do that? And then you had this beautiful response about Tier 2 and 3 vocabulary that I think set that up really well.

So how do you think about that issue of pre-teaching versus other ways of getting students familiar with more and more advanced vocabulary knowing that they’re starting often without a lot of that?

Marcie Samayoa (06:24):

Yeah, so I think pre-teaching is basically just giving the students a preview of the content and what some teachers can misinterpret that as is like, well, I need to teach the whole thing. And then I tell them, well, if you’re teaching the whole thing, you’re no longer pre-teaching it, you’re teaching. So we really want to be careful as to how we approach that.

I actually start with Tier 2 words. I’m a high school teacher, and even my students have a hard time understanding Tier 2 words. I explicitly teach them that by asking them to repeat after me. That way they know how to pronounce it. I’m in Los Angeles, so we have a huge ELL population.

Then afterwards, I give them a student-friendly definition. I think this is really important. It’s really hard to do. It’s not an easy thing to do, but you need to provide students with a student-friendly definition because if you pair the word with a difficult definition, the kids are just going to check out.

(07:22):

And then afterwards you want to put the Tier 2 words in context. So what I sometimes do is I give students everyday scenarios and I tell them, okay, from these list of words, which word best describes this everyday scenario? And so by doing that, you’re putting the words in context instead of just having them memorize the definition. Because you can memorize the definition and that is an important part, but if you don’t know how to apply it, then that’s where it starts to fall apart.

So I start with Tier 2 words, and then I introduce Tier 3 vocabulary through FASE reading. And through the FASE reading, the students get a preview as to what the Tier 3 words are, and they’re better able to understand it because now they understand the Tier 2 words. So that cognitive load has decreased. They’re like, well, I already know what Tier 2 words are, so I don’t have to focus my attention as much on Tier 2words as I’m reading.

(08:20):

I could focus more attention on Tier 3. So through the FASE reading, students get a preview of the Tier 3 words. And then after we do that together, I tell them to create a concept map using these words. That way they can make the connections and they’re applying the words instead of just memorizing the definitions. And then afterwards, we use it in context.

So now that students have gotten a preview of Tier 2 and Tier 3 words, and they have used it, now I’m able to use it in my lessons without overwhelming them because they already have an idea what those words are. And obviously students will forget, right? If we don’t give them a chance to retrieve the information.

So I include the Tier 2 and the Tier 3 words in a knowledge organizer. And throughout the unit we revisit that, and I have them study through retrieval, we do independent studying, and then they study with the partner for accountability and pairing all those strategies together.

(09:19):

I have seen huge success when it comes to teaching vocabulary, especially in science because science is filled with vocabulary. So when you do these strategies, you really want to focus on the words that are very, very important, and then the others just follow. Because if students understand the main words, then they slowly start to understand the other words. And so you don’t have to pre-teach all of it, just choose the important Tier 2 words, choose the important Tier 3 words, and slowly as you start applying these words, you can add more. And that’s how I approach vocabulary instruction in my classroom.

Justin Baeder (09:57):

Love it. And it really starts to chip away at this problem of, I have a word that I’ve defined, but all the words in the definition are unfamiliar too. Exactly. Tier one, tier two, and tier three words. Because I think we’re concerned about teaching the more advanced words in language, as you said, in student friendly language with vocabulary that students already have. If we’re trying to teach unfamiliar concepts, we have to anchor that in things that students already understand. So it sounds like tier one words are the words that students come in with, they use in everyday language, but tier two are a little bit more specific.

Marcie Samayoa (10:35):

All right. Tier 1 is words that students use in their everyday language, and they’re very familiar with it, so you don’t have to explicitly teach it. Tier 2 words are more specific, but it applies to all disciplines. So for example, the words apply, analyze, explain. Those are more academic terms, but they’re able to be used in all sorts of school subjects. Then there’s tier 3 where it is more specific to that subject. So for example, if I were to identify tier 3 words in chemistry, it would be proton, neutron, electron, very specific to science. So those are the differences between tier 1, tier 2, and tier 3 words.

Justin Baeder (11:23):

Those tier 2 words equip them to understand that reading better,

Marcie Samayoa (11:28):

And it gives them more confidence to read out loud too.

Justin Baeder (11:32):

So at this point, they don’t necessarily have clarity on all the tier 3 words they’re going to read about—the reading itself is their first introduction.

Marcie Samayoa (11:40):

Yes.

Justin Baeder (11:41):

And I think that gets around some of the paradox of how do I pre-teach this? When you really need to understand cells to understand what eukaryotic means, how do we unwind this a little bit? So you’re starting with the reading in that sense.

Marcie Samayoa (11:52):

Yeah, and again, it’s just to give them some background knowledge on it. And I think what educators need to understand is that vocabulary takes time, right? There’s no one activity where students are going to understand it 100% of the time because it needs to be used throughout the unit for students to eventually master tier three words.

So what the reading does is that it gives them the preview, and then after the preview, I also teach it through retrieval. I ask them to retrieve the student friendly definitions, but then we use them throughout the unit. And the goal is that by the end of the unit, we’ve used the words so much in context that students are familiar with the terms.

Because if you’re just focused on the definitions alone and you don’t ask students to apply those words, then it’s not really going to stick. It is really important to teach the words through context.

Justin Baeder (12:51):

Absolutely. And then you said that you’re layering on additional meaning by having students do concept maps. Is that right?

Marcie Samayoa (12:57):

Yes. Yes, yes, yes. I’m a huge fan of concept maps. It’s not an easy skill to teach. I have a whole blog as to how I address that. But once students have that knowledge on how to create the concept map, it is very useful.

I like it a little bit better than reading comprehension questions because what I found is that if you give students a list of questions and you tell ‘em to answer it using the text, what ends up happening is that the students just skim through the text and they find a word that matches with the question, and then they just copy it verbatim.

You could say, until you’re blue in the face, you need to put it in your own words. You need to put it in your own words. And what ends up happening is that students still try to test boundaries with that, but when it comes to concept maps, they’re forced to think about the relationships between the different words.

And so there’s not really a way to just copy it verbatim. They really need to think about the relationships when constructing a content map. And in addition, because no two content maps are the same, what can happen is that you give students time to independently create their concept maps and then have them share afterwards.

They have to do it on their own first, though. That’s the key thing here. And then you have them share after. And what ends up happening is that the discussions are rich because they’re explaining why they connected one word in one way, whereas a student connected it in another way, even though they’re both correct. So it really encourages a rich discussion between the students.

Justin Baeder (14:36):

Marcie, thank you so much for your time on this today. If people want to learn more about your website and figure out where to follow you, where’s the best place for them to go online?

Marcie Samayoa (14:45):

So I’m very active on X or Twitter. I like to refer it as Twitter.

Justin Baeder (14:49):

I still call it Twitter.

Marcie Samayoa (14:50):

Okay, good. So the handle on my Twitter is @SciInTheMaking, and my blog will be www.ScientistsInTheMaking.com. Originally, I started that blog to help science educators, but in my opinion, my humble opinion, cognitive science principles applies to all subjects. So everybody is welcome, and if they have any questions, they can always contact me through email, which can also be found on my blog.